Glenora

Protected by an early 1900s regulation, Glenora has virtually no commercial or religious development and is home to some of the earliest estates in the city.

Protected by an early 1900s regulation, Glenora has virtually no commercial or religious development and is home to some of the earliest estates in the city.

Malcolm Groat began working for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) at age twenty-five after signing on in 1861 in his home country of Scotland. He was posted to Fort Edmonton and was put in charge of the farming operations and packhorses. In 1970, after the HBC selected their 3,000 land reserve around Fort Edmonton, Groat claimed 900 acres of land along the western edge of the reserve for himself and retired there in 1878 with his wife Marguerite, daughter of Chief Factor William Joseph Christie, and their nine children. His homestead was officially endorsed when Dominion Land Surveyors arrived in 1881. Their property stood from today’s 121 Street to 149 Street, and from the river valley to 111 Avenue.

The town of Edmonton was developing rapidly when Groat sold much of his property to a real estate developer in 1903. It changed hands again in 1906 when James Carruthers purchased it. He named the area on the west side of Groat Ravine ‘Glenora’ and decided early that this would be a prestigious area. Carruthers limited religious buildings and commercial development in the neighbourhood, instead selling Glenora properties with the caveat that stated in part that “the houses to be erected on the said land shall be either detached or semi-detached and the sum to be expended on the erection of such house shall not be less than $3,500 [to] $5,000” depending on the particular lot. Carruthers also sold the new Alberta government land for the Lieutenant-Governor’s residence and invested in bridges across the ravines that separated Glenora from the new city of Edmonton. Council ran a streetcar line west in 1910 ultimately securing the success of the suburb. By the time the HBC sold off their reserve holdings in 1912 Glenora was home to many professionals; several of their original residences still stand with almost twenty listed as Edmonton Historic resources.

The neighbourhood is set apart due to Carruther’s caveats and the influence of the Garden City movement of the late nineteenth century. This trend promoted low-density residential lots and emphasized a parklike environment and the recreational use of areas like Groat Ravine. The sixteen grand homes facing Alexander Circle at 133 Street and 103 Avenue typify this movement. Likewise, the neighbourhood’s plan includes irregularly sized lots on streets that follow the flow and topography of the river valley and ravines, a sharp contrast to the grid system prevalent in the rest of the city. Some of Edmonton’s best architects were retained to design the period revival homes, post-war residences, and demonstration houses that populate Glenora.

From the outset, the neighbourhood was prescribed to be accessible to vehicles in part due to the relative distance of Glenora to downtown and the ability of its residents to afford such luxuries. Instead of relying upon a more common stable, for example, Dr. Robert Wells, whose residence stands on Connaught Drive, built one of the first carriage houses in the city. Some of Edmonton’s first garages were also constructed in Glenora.

Although highly influenced by its proximity to the area’s first homes south of Stony Plain Road and east of 135 Street, development of the northern portion of the community in the early 1920s contrasted to “Old Glenora” and its protection under the Carruthers caveat. The northern-most homes of Glenora face cul-de-sacs designed in the post-war boom of the 1950s.

The Alberta Government opened the Royal Alberta Museum in 1967 on the site of the Lieutenant-Governor’s residence. Due to the exclusive nature of the area’s residences, which were constructed with dancing, dining, and formal entertainment in mind, the museum is the only purpose-built cultural and entertainment facility in the neighbourhood.

Details

Sub Division Date

TBA

Structures

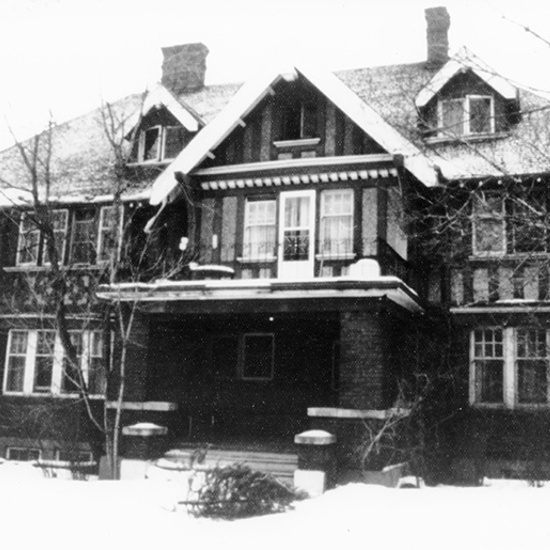

C. W. Cross Residence

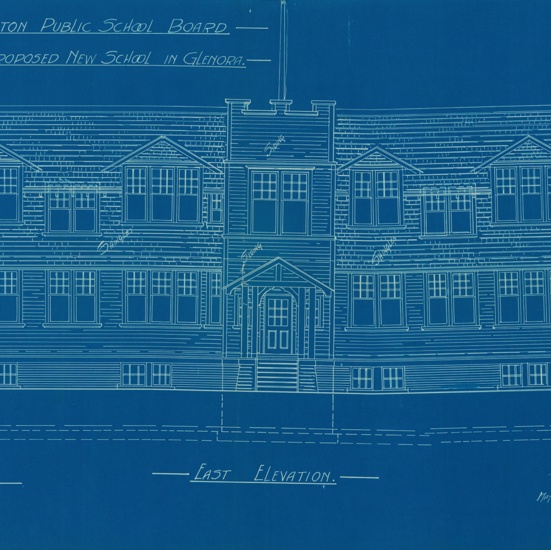

Glenora School

Glenora Substation- Station 650

Government House

Hyndman House

MacLean Residence

Old Glenora School

William Blakey Residence

Architects

Richard Palin Blakey

William G. Blakey

Robert Falconer Duke

John Rule

Ernest Litchfield

George Heath Macdonald

Samuel Mclure